After the relative excitement of Kava Night, Owain and I revived our travel ambitions and made efforts to see more of the Kingdom.

The majority of Tonga’s archipelago lays north of Nuku’alofa, spread between two island groups called Ha’apai and Vava’u, that together consist of more than 120 separate islands, three-quarters of which are entirely uninhabited.

We were told that some of the most spectacularly unspoilt scenery was to be found in the farthest reaches of the Vava’u group; but that it would take days of uncertain and, more often than not, unsafe travel to get to. Typically this would be all the more reason to go but given our time restrictions (our flight back to New Zealand was only a little over a week away) we opted for the closer Ha’apai chain and its administrative capital, Pangai on the island of Lifuka.

Tonga’s sole inter-island passenger ferry, and our mode of transport for the next 14 hours, looked as if it was built as far back as before the second world war, possibly even the first, and used in both as cannon fodder. It was a disowned Japanese vessel and, as far as I could tell, made from dented sheets of rust held together by some old rope and about seven or eight rivets. (Since my visit, the Tongan transport companies have added to their fleet.)

I later found out that it was the replacement for a ship named MV Princess Ashika which, in 2009, sailed into troubled waters 80km off the coast of Tongatapu and promptly sank. Reports following this tragedy stated that 74 people were subsequently lost at sea and that prior to the ship’s final launch a team of government surveyors chose to ignore the concerns of one of their members who deemed the ship unseaworthy. Finding all this out after the fact didn’t mean I was any less reluctant to board the boat the morning we set off from Nuku’alofa dock – I was forced to reconsider my ‘more danger, more fun’ theory of travel.

Sardined among hundreds of full-figured Tongans and their sacks and suitcases filled with food and personal possessions (the ship made this journey just once a week which meant anyone on it was usually gone for quite some time), Owain and I were conveyed towards the gangplank whether we liked it or not. I was ushered onto the propped-up walkway by the pointed end of one man’s umbrella gently pressed into the fleshy part of my bottom, only to look down and see that it wasn’t an umbrella but a machete, and that it wasn’t a man but an enormous pirate made out of trapezius muscles and menace. His tattooed neck was wider than my thigh.

I knew that Tonga was known informally as the Friendly Islands, but by this point it had seemed to me the man who came up with that amiable moniker had a good dealing in the ironic. Nevertheless, thanks to the massive pirate’s encouragement I made it up on deck quick-sharp and was one of the first to roll out my mat on a little spot beneath the tarpaulin. Regardless of how uneasy I felt about being detained on an extremely sinkable ship with a pirate for 14 hours, I couldn’t help but be utterly absorbed by the scenery.

It was a completely still morning and the sun was just about to cast the day in its full light. The placid purple ocean looked as flat and unmoving as a midnight delta, and a candy-floss-pink hue hovered just above a stark horizon and turned white, then grey, then cyan, as it rose into the sapphire sky. We leant against the handrail and watched the sunburst wash away these soft water colours, and replace them with fuller, more defined pastel tones. The boat withdrew from the mainland and sailed into an open sea, reducing our surrounds to just two striking shades of brilliant blue; and the silvery sundrops danced on the water’s surface, giving movement to a lifeless landscape. Now and again we’d drift passed scatterings of bosky islands barely bigger than a pitcher’s mound, crowded with dense and strangely neat verdure, and acting as our only measure of perspective for hours at a time.

Eventually the sun’s heat shewed us back under the plastic covering, where we lay with our backs against the steel hull, feeling the thrum of the engine ring through our limbs and watching the torn parts of the tarpaulin snap back and forth in the wind. By now the deck was full with bodies dozing on their pandanus mats; mothers cradling their newborns; fathers entertaining toddlers; teenagers listening to music; and Owain and I lodged in the middle of it with an elderly man reclined beside us sharing his burlap sack of breadfruit to use as a pillow.

Eventually the sun’s heat shewed us back under the plastic covering, where we lay with our backs against the steel hull, feeling the thrum of the engine ring through our limbs and watching the torn parts of the tarpaulin snap back and forth in the wind. By now the deck was full with bodies dozing on their pandanus mats; mothers cradling their newborns; fathers entertaining toddlers; teenagers listening to music; and Owain and I lodged in the middle of it with an elderly man reclined beside us sharing his burlap sack of breadfruit to use as a pillow.

I was as cramped as I might have been on the 8am out of East Putney, but not nearly as uneasy. In 14 hours the atmosphere never felt particularly affectionate but the indifference shown us by this community of passengers was in a way inclusive, which made it seem familiar and neighbourly. And not one other person stabbed me in the arse with a machete.

As the downpours kept coming it was pretty clear the miserable weather that welcomed our arrival wasn’t going to change any time soon. Consequently, a fair few hours were spent cooped up in the communal room making brews and shovelling ridiculous amounts of Rich Tea biscuits down our throats. While this put a hold on exploring the island, it did give us ample time to get to know our fellow lodgers – most notable of all was the middle-aged German pairing of Tomas and Gert.

Tomas was an outstanding booze hound. At best, conversations with him would be baffling, but generally vexing. This was primarily because he’d led such a fascinating life but had become so chemically inconvenienced by years of self-abuse that he couldn’t form coherent sentences long enough to tell about it.

After several attempts and many prying questions I was able to gather that he had been living in Tonga for the best part of 20 years, and started out as a highly respected pastor at a nearby Roman Catholic church where he regularly preached to a devoted congregation back when he was just 21. His dependency had since gotten the better of him and was forced to give up that prodigious post, although he still gets invited back each Sunday to play the organ.

Tomas was not a man of domineering stature – he stood at around 5”1, but due to the nature of his vice that wasn’t very often so an estimate is all I can volunteer on the man’s height. His shoulders were narrow and sloping, and his back curved in a way best described as Gollum-ish and on the end of his enfeebled arms was a set of swollen spade-like hands covered in calluses, broken skin and scars.

His forearms were stippled with tattoos he’d applied himself, and one on the back of his left hand was of a date drunkenly (I’m assuming) scribbled below the name of a town in northern Alaska he’d visited during a trip to the Bering Strait. Although he was physically incapable of talking about it, you knew from his appearance that his life was not an easy one.

It was difficult to guage what kind of a man he was as he did very little besides quietly shuffle around the hostel grounds by himself. Sometimes so quietly it would take minutes before anyone realised when he’d taken up a seat right beside them.

At night, Tomas came alive. Not to everyone’s liking mind you. Well, anyone’s really. Most nights were spent listening to him wail over his guitar long into the wee hours, only stopping occasionally to argue that he didn’t want to stop playing and go to bed and that he wasn’t in fact ‘fucking terrible’.

His compatriot, Gert, was a stark contrast to Tomas in many respects but equally unusual in appearance. Lanky like Peter Crouch, he towered over Tomas at 6’8 – and every inch of him was miserable. He had a dedicated Teutonic restraint and a face deficient in almost all expression besides general displeasure. Too much time spent with Gert would leave you a little less than deflated, hence the ridiculous amount of Rich Tea biscuits.

Seeing as we were holed up for the foreseeable, Owain and I took up the offer of joining in on the ‘famous Kava Night’ held by Danny, a young Tongan gentleman employed at the hostel. It turned out to be little less famous than we were led to believe as, including Danny, the total attendance was three. Which makes Kava Night about as famous as BBMak. However, we were intrigued to find out more about this intoxicating elixir so we sidled up next to this smoothly-spoken storyteller who regaled us with Kava-inspired myths and tales while serving us up all we could drink.

It tastes a lot like muddy water (not whisky, actual muddy water). My guess is this is largely due to it being extracted from a root which has been gathered from a muddy field, chewed up and spat out by virgins and then arbitrarily diluted with rain water. Admittedly it doesn’t sound like the most appetising beverage in the world but I’ve drunk cans of Carling at a club in Merthyr Tydfil before, so I had no excuse.

It is tradition for virgins to chew the root as back in the day there were no machines to do it and apparently no other people with teeth, due to poor oral hygiene, which evidently went through the roof once the sex was had.

Although there doesn’t seem a whole lot to Kava, this rustic tipple packs quite a punch. After only two cups my tongue began tingling. After three cups it started pulsing. After four it took all my concentration to keep the thing from rolling out onto my chin. Five cups in and I was noticeably drooling, and after my sixth I was acutely aware of the numbness setting into the entire left side of my face.

With one eye open I looked across the table where Owain appeared comparatively composed, although he did seem to be grinning quite a lot and I don’t remember Danny’s stories being particularly funny.

To Danny’s disappointment I declined my seventh cup only for Tomas to interject with an animated bid to take it off my hands. This shocked me as I was completely oblivious of Tomas being anywhere near us – he must have ghosted his way in at some point without any of us realising. I turned around to see him staring wide-eyed at my cup of Kava with both hands outstretched.

I happily gave up the last of my serving and Owain soon followed suit, and then we both watched as Tomas gleefully saw off cup after cup of the stuff as if it were fruit-filled glasses of Um Bongo.

With heavy legs we all lumbered back to the communal room where Gert was sat looking very displeased about something or other and Tomas got out his guitar. The next morning the left side of my face became responsive again, which was timely as it was raining and I had lots of Rich Teas to get through.

Before lunch Barry asked me to fill the 4-wheeler’s spray tank with 100 litres of Bloat and spray a paddock on my way back to the house. Bloat is a herbicide used on young grass to prevent the legume content killing the grazing cattle.

I went about the job as I had umpteen times before – phlegmatic and routine-like. After a brief but recent spell of rain the weather was growing clear and cheery. The air felt fresh and it blew with a gentle spring crispness.

Tootling along the upper fence line I watched yellow strands of sunshine fall between parting clouds and glint on the surface of the wet grass. Reaching a bend in the fence I turned and climbed a slight incline.

Throughout most of the spring season I found myself contesting with a strange and violent wind that would whip in from the east and try to blow the herd clean off the hill side. But, today it seemed in playful mood.

The giddy winds painted quick brush strokes across the canvas of the landscape and the clearing sky gave a marvellous freshness to the colours – a myriad of blues, yellows and greens. It was the kind of mid-morning that would make you thankful for a life outdoors.

Ahead of me now the paddock grew narrow as the fence-line turned downhill. It led to a small patch of the paddock barely big enough for 6, maybe 7 cows, before doubling back along the bottom. The bottom fence-line ran parallel with the track, but overhung it by six or seven feet.

Knowing what I do now, avoiding this patch would have been a sensible choice, but not wanting to seem negligent (after recent events, I was making a concerted effort not to kill any cows) I steered towards it. Approaching the back side, I saw that the paddock took another turn downward, only this time shorter and sharper.

I gave myself too little space to properly manoeuvre and I’d noticed too late to pull out. I pressed on the brakes but the extra weight of the spray tank rendered them useless and the tyres skittered over the slick turf beneath. Being forced towards the fence my immediate reaction induced me to pull the steering back uphill, but despite my efforts I couldn’t regain full control of the bike.

I felt the two right-side tyres lift off the ground and the bike tilt towards the drop to my left. The wind turned wicked as a wild squall rattled through me like an almighty wave. I drew the steering back downhill to right the bike, but this meant heading squarely back towards the fence. With nowhere else to go, again I turned uphill; and again the tyres lifted into the air. I had no another option, and now I was out of room and out of time. The tyres kept lifting higher and higher; and the bike kept tilting further and further – I knew it was hopeless.

A kind of breathless hush took over as the wind, the sun, the clouds, and all of nature paused and focussed in on the bike teetering on two wheels. I released my grip; rose up out of the seat; and with only the toe of my left boot resting on the pedal I seemed to hover weightlessly waiting for the fall.

The next second I was laying face-up, trapped in a ditch between the bank and the track, watching the bike crash through the fence. The peaceful silence was shattered by two tonnes of machinery tumbling down towards me. It was now as if time was catching up with itself as the next moments happened in a flash of panic.

Unable to move right, unable to move left, all I could do to avoid being crushed was to throw my legs over my head and roll backwards. The bike fell so quickly I had only managed half a roll when its full weight struck the base of my spine with the force of swinging sledge hammer.

The impact punched the air out of my lungs and detained it in my throat. I kicked out my legs and clawed at the dirt. Eventually, after what seemed like minutes, my lungs relaxed and I coughed out a breath.

A frightening numbness took over my body: the pain was indistinct but I knew I wasn’t able to stand up. Managing to regulate my breath I could hear the frantic beat of my heart steady in my chest. The bike had rolled back onto its wheels in front of me with its engine still rumbling. I reached into my pocked for my mobile to call for help.

On almost every day previously my phone had been able to get about as much reception as a bar of soap and so I was relieved when it connected to Barry. Were it not for this mini miracle it was figured I would have been lying there for another three hours before someone would have found me.

Two ambulances arrived within fifteen minutes. The medics cut me out of my overalls and administered a substantial dose of morphine which seemed to put rather a rosy aspect on things.

After an X-ray it was discovered I had crushed three vertebrae in my lumbar spine, and was therefore prescribed a strict course of morphine, codeine, and other wonderful sedatives.

I’ve never stuck to a diet more rigorously.

It hasn’t escaped my attention – and likely not yours – that these reports of my farming experiences have been fairly dominated by episodes of a bungling nature. Recounting tales of such amazing ineptitude makes these occasions seem like they had, in a way, a purpose. Hindsight lends these stories an air of pleasantness. Something they certainly didn’t have at the time.

So, you may have come to expect another thousand + words of folly and dim-witted carry-ons – but this time you’d be wrong. This time it will be less than a thousand words.

Those of you who read the first Dairy Diary might recall that I’d managed to secure this job under the pretence that I was able to ride a motorcycle. A pretence discovered within minutes to be false. This liberal use of the truth had succeeded in landing me an income, but, it did even better at landing me in the muck – figuratively and otherwise.

I became acquainted with my bike.

The first lesson was starting the engine. This is begun by positioning yourself with your legs either side of the bike and sitting in the saddle. You’re to follow this by placing the key in the ignition and turning it clockwise. Then, with every ounce of strength, wildly pump the kick-start lever with your left leg three to four hundred times; or, until you’re just about ready to roll the bike off the nearest cliff.

If you’ve resisted the temptation of fetching a sledge to it and the engine has actually started, you can move on to the next phase. Pulling away on a bike like this is all about mastering the balance between control and timing – not easily done with something that infuriates you to the marrow.

Several attempts at this would generally have me revving the engine so high it sounded like a low flying Airbus, then, mistiming the clutch-release and sending the bike off unmanned into the barn wall. Eventually, gradual progress will be made when your paycheque depends on it.

Providing you want to go faster than 5 miles per hour, you will need to know how to change gear. To me, 5 mph seemed ample, but I was told otherwise and instructed to learn. Each person has their own method for changing from one gear to the next and my own can best be described as iffy.

Mounting the bike I found quite easy. But, not nearly as easy as dismounting. This was the part of the sequence that came most naturally to me. So much so in fact, I often accomplished it without even the slightest intention. And, I might add, at quite some speed. Even as a perfect novice I would find no problem in leaving the bike within 2 seconds of getting on it. Some might have said I was gifted.

Once you’ve grown in confidence enough to attempt to cover a good distance, a mysterious transformation occurs upon the surface you’re travelling on. What once looked as flat and accommodating as the M4 suddenly becomes riddled with bumps, potholes, stones and rocks big enough to jack knife an Australian road-train.

Under operation of a novice the bike becomes as accurate a tool at detecting these blemishes as a carpenter’s spirit level and navigating any stretch of track on one of these machines becomes a tooth grinding experience.

It takes weeks of practice and several consecutive days free from accident to convince you you’ve now acquired the art of motorcycling on the farm. But, it takes only a moment to prove you’ve actually acquired nothing of the sort.

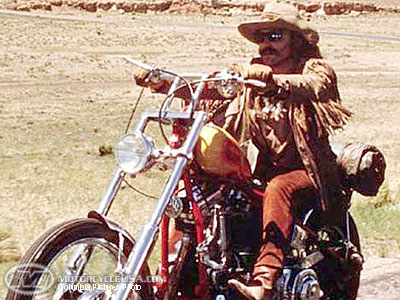

Motoring along at a handsome speed one day – my attention firmly committed to an Easy Rider fantasy: as is the wont of all newbie motorcyclists – I presently traversed an average sized boulder and took to the air quite apart from my bike.

Very rarely did drifting off into these boyish reveries improve my biking circumstance any. It did perhaps the exact opposite. On occasion, even the most basic of manoeuvres managed to present me with great difficulty.

Rounding a bend while sounding out the second verse of Born to Be Wild the bike encountered a steering issue that had developed into a jerky zigzag before I’d realised I was in trouble. It was my natural instinct to wrestle with the handlebars in such a way as to almost pull them out of their sockets. This helped in no way. And at last the machine went slanting for the ditch in direct defiance of my efforts and cast me abroad to test the resilience of a fence post. It passed by my account.

At least one minor biking incident would occur on the farm almost every day: from my first to my last – definitely on my last.

I hope I’ve been able to furnish the reader with a fairly comprehensive introduction to most characters at work on the farm – they’re a curious bunch. One of the characters I haven’t yet mentioned, however, is Baz.

On general appearance he doesn’t offer much to be taken with. His hair is highly unkempt and often clogged with dirt. He has little control over his own saliva and his breath smells like a rubbish tip in August. But while I find it peculiar how excitable he gets at the site of a moving vehicle, most of these characteristics can be forgiven by and large, as Baz is a dog.

To degrade Baz in any way would be an injustice as he is no different from any other full spirited quadruped and, quite often, a well-meaning, conscientious worker under proper instruction.

He is, generally speaking, of a pleasing and likeable nature, when all is well and good, but, can occasionally be the object of certain people’s distress, when it isn’t. I found myself relating to Baz quite closely.

When Brian asked me to use him as help to get the small herd to Barry’s milking shed the next morning, I was glad for the prospect of working alongside him.

At the end of a very trying day Brian gave me detailed instructions on getting the cows on to the track, as apparently there was a sheer sloping bank they would need to avoid. If you’re not familiar with Brian, you should be made aware that his instructions are both unique and useless, in measures favouring the latter.

“You’ve got to follow the herd at the front so that you can lead from behind them.”

“Umm…OK…”

“There will be a small hill. Walk up it till you’re at the bottom.”

“How do I…?”

“If you look down above you, you’ll see the fence that’s not there anymore.”

“Wha..”

“Near it is another hill. DO NOT WALK UP THIS HILL!!”

“Yes. OK. No problem.”

“So, once you’ve walked up that hill…”

“Jesus.”

“…quickly, push them as slowly as you can, and they should walk through the front gate at the back. Easy.”

“……..”

“You’ll be back to where you finished in no time. OK?….Andy?”

“….Yyyyeeesss. Goodnight.”

My alarm sounded at some rude hour and I woke with my morning routine in pitch darkness. This invariably meant either, stepping on a plug, upending a footstool with my shin, marrying a table corner with my crotch, or, all three consecutively.

Outside, I collected an unusually calm Baz from his kennel and we both set off down the track on my scrambler. He was in quite good shape, considering the hour. Which is more than can be said for my crotch.

Hopping off as we pulled up, Baz sauntered over to the paddock with the self-assurance associated with someone very aware of their responsibilities, and sat upright with a lordly air waiting to be presented with an open gate. This buoyed me somewhat as Brian’s instructions only served as means for a piercing headache and I now grew confident that Baz might just have it covered.

Still half asleep I lazily pushed the bike to the side of the track as Baz coolly trotted back towards me. Not a word was spoken, but I gathered from his facial expression he might have said “I’m sorry Andy, but we haven’t all day. Time and tide wait for no man and all that. What say we get this show on the road?” And at that he turned and went back to take up his position at the gate. “Thank, God” I thought, “Baz has definitely got this.”

Opening the gate I was taken by an insuppressibly deep yawn that for a moment suspended most of my bodily functions and caused me to briefly blackout. On recovering my senses evidence of this blackout formed before me as Baz was now some distance away, tearing across the horizon at a rate not too far south of 30 miles an hour, terrorizing the entire herd. Startled into action I gave chase.

The very second I raised a shaking fist and motioned to issue a verbal protest I realised I hadn’t the first clue of what to say. Baz had been trained to respond to a particular set of commands, of which, it now dawned on me, I knew none. The next three or four minutes I devoted to screaming his name only seemed to act as encouragement.

Baz’s running had started to look a lot more like frolicking now and his face was beset with boundless joy. Gambolling about, prancing from one terrified cow to the next he’d completely lost any sense of the composure I had been banking on to help me.

My temper began rising, by steady and sure degrees. And as control was getting away from me I fell to muttering some vicious comments under my breath, and then exclaiming some more above it; quite far above it.

Finally, with a venomous access of irritation, I made an attempt to put a rein on this hysterical mutt and bound with a brisk stride down the steep slope after him. At some point shortly before my third step I was forced to submit to the severity of the slope’s angle and navigated the rest of it on my face.

At the bottom, fairly humiliated, I picked the grass from my teeth, and began on one of those ridiculous foot races around a paddock I have, by now, become so very used to, but no less exasperated by.

For some reason, probably founded in delirium, I hoped that at some point in the dog’s short life he might have developed a human understanding for sympathy, to which I was now obsequiously trying to appeal. Anyone who knows canine nature needn’t be told that by this time Baz was thoroughly enthralled in this exercise and no amount of my pleading would persuade him of another employment.

Standing at the slope’s peak, wheezing like an asthmatic pit donkey, I watched Baz and about 150 cows act out a scene of perfect pandemonium. I slumped onto my rear and hung my head defeated. The sound of Baz’s barks echoed through the valley as the morning’s silvery light began to tint a soft amber.

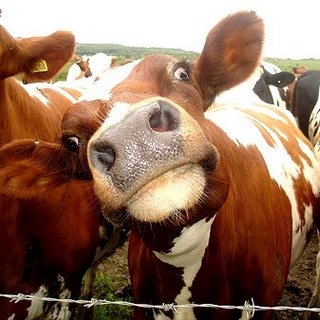

The herd had scattered across all parts of the field I could see, and across many others I couldn’t. A small group were stranded halfway up the slope, with an impossible climb above and insufferable dog below. Outside on the track one slightly addled cow looked back over her shoulder and seemed to be thinking “Err…is this not the right way? I suppose I’ll just wait until you’re ready.”

Even at this hopeless stage I was actually thankful of the fact that I was completely alone. For one reason: I had no option but to get up and try again, and for another: no one witnessed me nearly brought to tears by a Border Collie.

Despite the proceeding exertions being every bit as gruelling, I’d managed to turn things around and return some semblance of order. With the sun now up and the best part of an hour gone I was following the last cow through the gate.

On the track, grinning like a Cheshire cat was Danny casually spectating from a reclined position across his bike. He was obviously quite tickled by the whole episode and made no attempt at concealing it. This was an understandable reaction, as my plaintive demeanour was worthy of none besides that one. Understandable: but only in hindsight.

Arriving at Barry’s milking shed later than any one had ever arrived before, I should have expected to be on the wrong end of a fairly sharp ticking-off. Yet, when presented with Barry, I just blamed Baz, and I got off scot free. Ha. This turned out to be a gambit I would exploit on more than just this occasion.

Sorry, Baz.

I would love to admit that after a tough few weeks toiling amongst the muck and mud, I had, with a hearty show of pluck, managed to surmount my hardships; that I had built up a mutual respect with my colleagues which catered us all for a happy and fulfilling experience.

The truth is the hard times continued, and the only sense of solidarity came from the rest of the team’s contempt for me. My softened attitude and mild approach to handling their disparagement only seemed to encourage more. “It was so dark this morning I spent 20 minutes trying to herd a tree. Ha ha ha…what fun!…Anyone? No. Okay, sorry I was late.” This wasn’t long in wearing thin as 50 year old dairy farmers don’t have much patience for young upstarts and their not-funny excuses.

By about midway through the second month I had somehow accrued quite a startling amount of mishaps. Most notable of which would be nearly decapitating a cow with the rotary shed platform: the blame for which I found quite difficult to parry. Accidentally chopping off a cow’s head calls for a blunder too conspicuous to ascribe to a humorous little misjudgement, so it would seem.

Unfortunately, this wasn’t to be the only cow I would nearly kill as on one particularly dark morning I inadvertently left one behind, only to find her later dying of milk disease. Things were not going my way. It soon became rather apparent to everyone that their most recent acquisition might not be totally conversant with the ways of the country.

This led to me questioning whether I would last the length of my contract. I had never before felt that so much of my input was to the detriment of the team and the thought of drawing it out twisted my stomach in knots. The tensions rose and eventually culminated in an argument between Brian and myself over whether the state of affairs could be resolved. Several days passed while I see-sawed with the idea of a reluctant, early exit. Until, to my immense satisfaction, I found out that Brian and Barry both tallied quite well with their very own lists of farming faux-pas’. Brian had recently, and quite magnificently, managed to topple a three tonne tractor down into a valley; while, one morning, Barry had left not one cow behind in a paddock, but seven. How do you not see seven cows?

This news came to me as a great relief and one that gave my confidence a healthy hoist to haughtiness. I wasn’t about to fool myself into thinking I was anything but a strictly average farmhand, but I did allow myself to question whether I was quite as bad as they made me out to be.

By this stage, I hadn’t seen eye to eye with Barry on anything. We couldn’t seem to relate at all. He was the kind of character that were he in a good mood, it would be rare and short lived. When he wasn’t put upon by a heavy workload, or subject to even the slightest of misfortunes he would come across as quite an equable and intelligent fellow.

Conversely however, he was afflicted with a fuse shorter than a spoilt toddler’s. When something wasn’t done exactly as he expected, or he didn’t get his way, he lost control of his senses and descended into a fit of petulant rage: screaming at anyone, kicking the ground, throwing things, and quite often telling me or Danny to f*** off. So, in light of the recent news, during any future fuse shortages, I felt a retaliation could be justified.

After breakfast one morning, Danny and I were given the task of bringing in the day’s only cow and calf from the heifer’s paddock: a relatively relaxed job by most accounts. However, Brian’s instructions alluded to the difficult nature of this particular cow, Lucy, as he described her as having a tendency for erratic bursts of excitement. I felt I was qualified for the job.

At this time in the season the herd was dwindling so not ten minutes had passed before Danny and I had separated Lucy from the rest and walked her halfway to the gate. So, as I was happily planning my lunch, in bowls Barry, roaring across the paddock on his scrambler. Lucy stops stiff in her tracks and fixes a stare at him careering towards us.

Barry had rushed over to the paddock to help us, as it was thought impossible we could manage without him. But his enthusiastic entrance only sent Lucy spiralling into frenzied chaos. She started frantically sprinting back and forth, round and round, everywhere except through the gate. Barry hopped off his bike to join us, and for the next fifteen minutes three men in wellies and an excitable heifer ran in circles, chasing one another across a field, like some kind of confused Benny Hill sketch – much to the bemusement of the nine other cows now watching.

As Barry started barking orders and telling me to ‘wake up’, as if the reason Lucy was still in the paddock was because I wasn’t running and shouting enough, I enquired as to whether he was perhaps ‘having a laugh or what?’ (or, words to a more hostile affect).

Lucy had made it patently clear she did not want to leave the paddock, and all we’d achieved was to exhaust and irritate ourselves. As frustrated as I was, no-one was more furious than Barry: he’d slid into one of his episodes.

In the event, he paid little attention to Danny or I, and so continued in his quest to persuade Lucy out the gate, now with a stream of pettish verbal insults, such as ‘Just f*** off and get out!’ and ‘Where are you going now, you fat b****?’, and then ultimately resorting to just hurtling clumps of dirt at her head. Lucy, however, didn’t seem to understand quite what he was driving at so made no attempt at leaving the paddock. As it turned out in fact, Lucy decided she’d stay where she was and just eat a bit of grass, instead.

Minutes later, even with the foreman being as much help as a Broadmoor patient, we’d tentatively coaxed her to within meters from the gate, only for the capricious little heifer to make a sharp U-turn and come right at us. This time she was charging like a rhinoceros and I wanted no part in stopping her. Danny had also given up the goose, but Barry wasn’t to be outdone.

The full application of his anger seemed to have overtaken him entirely. Danny and I stood with feet planted, arms at our side and jaws agape as Barry drew a breath, hunched his shoulders and threw himself head first at all 600 kg. I was dumbstruck. But it came as no surprise to any of us – least of all, Lucy – that he was duly pole axed ground ward at the speed of a bullet leaving the barrel. He lay heaped in a Barry shaped hole and the ‘episode’ was over. His pride eventually heaved him up onto his feet and he stood for a few seconds silently trying to work out how many of his internal organs were failing before he staggered back to his bike. Danny and I shared a sidewards glance and carried on with the job.

Not a word was spoken for the next ten minutes as we eventually walked the cow out through the gate and along the track. From that point on it wasn’t all roses and butterflies but there did appear to be a favourable attitude shift that proved promising.

Each week I was allowed one glorious day’s relief from the duties of the farm in order to get some much needed R and R. Given the available opportunities for entertainment this would usually consist of either sitting in a chair listening to New Zealand Radio (not advisable for anyone with a wall close enough to beat their heat off), sitting in a chair partaking in thirty to forty rigorous games of Solitaire, or just sitting in a chair.

This week, however, was to be different. This week I was finally going to explore the sites and sounds of the great township of Tokoroa. However, I was to discover these would be exhausted inside seven minutes. There’s two of them. Neither worth mentioning.

Standing on the pavement outside the courthouse (easily the busiest building in town that morning) I was at a loss for ways to spend the rest of my day. I remembered what Brian’s son, Barry, had suggested in the event of getting bored (a safe bet). It was to take in a movie at the independent cinema located behind the police station, which is where I went now.

In finding the cinema I wasn’t entirely surprised to be presented by a dilapidated building with several of its windows either cracked or boarded up, and a closed sign hanging from the entrance. Upon closer inspection, I wondered if in recent times this sorry looking structure hadn’t so much been used as a movie theatre as much as it had been used as a latrine.

Thankfully, because the centre of Tokoroa is 15 kilometres from the farm and it had taken me two hours to walk there, a local pub was opening just as I had decided now would be a good time to start drinking. This was an idea I seemingly shared with six or seven of the local residents who were already inside and waiting to greet my arrival with a deathly silence and a threatening look of disdain. I immediately felt like the lone stranger from a Spaghetti Western movie and I’d just walked in to a tavern that don’t take kindly to my sort. Stifling the urge to loosen my collar and slowly retreat back out the entrance, I fixed my gaze at the floor and shuffled towards the bar.

I ordered a draught beer and hoped that the rapacious looking barmaid wouldn’t fill up the glass just to throw it in my face. Fortunately she didn’t and I was able to a pass a couple of happy hours drinking cheap beer while watching three highly inebriated gentlemen battle with the laws of gravity.

I stood to depart just as the men were languorously accepting defeat and went to the only internet café I could find in order to check-in with the civilised world. The sign for the café – written in pencil on the back of an A4 piece of scrap paper and taped to the inside of a murky plate glass window – directed me through a single closed doorway that opened onto a dark staircase and up to another closed door.

Unsure whether I had the right place, I tentatively pushed on the handle and peered through to what was a lone woman sat at a bare desk in the middle of a hugely empty office space. Even more unsure of this being the internet café, I stepped inside and approached the lady who still hadn’t looked up from the single sheet of paper placed in front of her. “Excuse me”, I whispered in my most polite and non-threatening voice, to which she responded by lifting her eyes off the very important document to shoot me a stare from over the top of her glasses that said “And what the fuck do you want?”

I could see she was a busy woman so quickly explained I was looking for the internet café. Her mood was instantly conciliated. She couldn’t wait to get me onto a computer. With smiles and nods she ushered me across the empty floor to the corner of the room where three of the first computers ever made were waiting. They looked as tired and worn out as the three drunks I’d just left wallowing in the bar downstairs.

I say it was three computers – it was actually two computers and three monitors. A fact that eluded the lady for whole minutes while she stared at her reflection, mystified as to why it wasn’t responding. So we put our heads together and eventually tried using one of the computers plugged in, and I was finally on the net.

I was on the net but going nowhere; the pages loaded so excruciatingly slowly I wished I’d brought a book; or a noose. I think I was able to check one email before I started to regret leaving the pub, so got up and left. The now chirpy “internet café” owner seemed completely unabashed in charging me $4 for this and I belatedly understood why she was so happy: $4 would have done wonders for the profit margins on a place like that.

Walking through the streets of Tokoroa, particularly on a Tuesday afternoon, is depressingly grim. Everyone has that same dispirited look of desperation draped across their faces. One that gives the impression of intense boredom while being in the knowledge that there’s nothing they can do about it, aside from drink. So that’s exactly what I did. I drank. I drank a lot.

Subsequently, I don’t remember the name of the next bar I went into, but I do remember that it was completely empty. When I stepped inside and stood in the doorway, I was comforted by the fact of there being no chance of a kicking, so decided I’d stay. Besides, the fact there was no-one in there actually added to the atmosphere. Hearing the barmaid step out from the back room, I turned towards the bar.

Walking over I became oddly confused by something that appeared to be forming on the front of her head. I was sure it couldn’t have been what I thought it was, but it looked a lot like the intimations of a smile. I ordered a pint and studied her face for a few more seconds. Yes, she was definitely smiling. “Fantastic!” I thought, “This deserves a drink”. So I bought another pint; and then another; and then enough to supply an evening with Mel Gibson and Orson Welles.

I started extending a few pleasantries her way which seemed to be fairly well received so chanced to venture the idea of conversation. It was speedily declined but I was, at this point, impervious to rejection, so nobly retired to a table beneath a wall-mounted television. All in all, I wasn’t having a terrible time in Tokoroa; which, in hindsight, might have had something to do with the alternative of being shat on by several cows as the basis for comparison, but, nevertheless.

Propping myself onto folded arms, there I spent an indeterminate amount of time either watching television or studiously inspecting the inside of my pint glass. Sometime during the second half of what I think might have been a rugby match, but could just as easily have been a program on Antelope, a raucous rabble of miscreants came in and joined me at my table.

One, the tallest, stood wearing Aviators and a toothless grin. Another, the stockiest, sang and drooled over the acoustic guitar he brought with him. And the fattest sat judiciously coaxing an unruly hamburger onto most parts of his face. I knew I was drunk, but these gents were off the scale. We began with some incomprehensible introductions and moved directly onto the topic of rugby – a topic I know as much about as I do The String Theory.

However, as a Welshman, I do know enough that when someone disparages the Welsh team, I am to react with a resounding and guttural reprisal, and then probably a song. Miraculously, on this occasion, I still had the clarity of mind to quickly tot up the ratio of Kiwi’s to Welshmen as 3 to 1, and to note the striking size of their forearms as a significant component in their argument. I decided they were making some astute observations and took to agreeing with them all. As the conversation stagnated I fell quieter and took up quite an interest in the many text messages I was now pretending to receive.

When the time came, I hoisted a farewell hand and waved it in the general direction of everyone at the table, which, embarrassingly enough, wasn’t acknowledged by anyone, and turned to take my leave.

After several faltering attempts at the door I noisily clattered back into the street only to be almost immediately thrown back in again by the searing sunlight now ripping through my retinas. Once my composure and eye-sight returned I checked the time to see that it was barely after four o’clock. Now that I was suitably dishevelled and thoroughly convinced I had exhausted all possible avenues for excitement I thought it sensible to take myself home.

In order to allay Brian’s concerns regarding my tenure under his supervision, I made attempts at appealing to what I hoped was his empathetic nature by displaying a childlike enthusiasm for the job. “Don’t fire me, Mr. I’ll do better. Sure I will.” That was basically the foundation of my argument. I accented this plea by never being further than 3 feet from his side; showing how keen I was to try my hand at anything. I was consequently told to go away a number of times, but I this was only after he understood. I know this, because he told me.

As it happened, from the first week on I was never left wanting for something to try my hand at. It was now the beginning of August and the start of calving season. This meant that each of the 700 cows was going to have a little cow of their own, sometimes two; and over the coming months I was going to be helping. This would involve a number of jobs of varying description and liking but, for the purposes of the blog, can be condensed into these.

1. Calf retrieval – Once the calf is born – usually over the course of the night – I am sent into the paddock to locate the mother, who has been described to me as ‘white with black parts on her’ or sometimes with a slightly more concise description of ‘the brown one’. While it appears that everyone else knows which cow to target, I am generally running with both arms raised above my head towards a collection of innocently grazing cows. Once she has been located, I am to separate her from the rest of the herd – more often the case against her will – and coax her out on to the track.

At the point of completing this phase of the task I have likely run several kilometres chasing upwards of 10 separate cows, none of which have birthed, through a paddock riddled with holes big enough to get swallowed by and logs and broken sticks hidden in long grass that possess to be the perfect instruments to administer a dislocated knee. As long as I haven’t found myself at the bottom of one of these concealed openings in the earth I am now put to retrieving the new calf.

Providing luck was on my side the infant would be curled up in a restful slumber in the middle of a low lying and flat section of the paddock inches from the gate. I remember this being the case once, and never again.

Convention would have it several hundred yards away; sometimes not in the same paddock; sometimes not in the same farm; standing at the highest point of the horizon briskly limbering up for the chase of its life. By the time I have reached the calf and regained composure enough to breathe without the sensation of my lungs collapsing, I take a minute to study its curious countenance while it makes preparations in front of me in the form of quad stretches.

What follows is a good 10 or 12 minutes of exasperating pursuit – up hills and down banks, over logs and through bogs, and if I’ve not been drawn at least once into a head on collision with an electric fence then it’s been unusually fortuitous.

The final stage of the proceedings is for me to carry said calf back across the hillside to the trailer. The demand of this can only be appreciated when it is understood that newborn calves can weigh up to 100 lbs, depending on the breed. One calf of a particularly tremendous dimension was birthed by a cow with the significantly apt nickname of ‘Tank’. Danny carried that one. And this task is to be completed as many as 15 times per day during the season’s busier weeks.

2. Transporting the cows and calves – Up to seven or eight calves can fit into the trailer attached to the back of the 4-wheeler at a time. The trailer is then driven at a speed of less than 5km/hr with the objective of persuading the birthed cows down the track behind it, and back towards the direction of the milking shed.

If we now consider the simplicity of a cow’s mind with its usual and somewhat unexceptional day to day existence, we shouldn’t fail to remark upon the potentially distressing effect this task may have on a new mother. Essentially, I have just, without reason or explanation, singled her out of a crowd of her peers and chased her like a maniac out of a field in which she was understandably recovering from a taxing night of labour (100 lbs!) onto a grassless track and left to wonder what that was all about.

She has then bore witness to the very same man wrestling her new born to the ground and throwing it into a caged trailer where it is left to cry-out while it is stood and defecated on by seven other screaming calves. At this point it can be ascertained by the nervous pacing back and forth along with the distended eye balls protruding from her skull, that this mother’s sensibilities are now a bubbling tumult of confusion and agitation.

However, the episode of distress hasn’t quite reached its end as now is the moment the individual, and unquestionable cause of her anguish, mounts the 4-wheeler and parades the young in front of her at a speed that forces her to suffer this scene for perhaps over an hour; after which the calf is swiftly whisked away from her and summarily disposed of into a pen filled with other similarly fated calves.

It is entirely understandable, almost logical, that the trip back to the milking shed is significantly comprised of frustrated attacks from said cows against said individual.

3. Drenching – This job is required in order to replenish a cow’s diminished calcium levels after they’ve given birth. The process is simple in theory – feed each newly calved cow one bottle of molasses. In practice, you’re lucky to get the job done without losing the use of an arm.

Before this can be attempted all the cows will have been herded into the herringbone and locked up tight to one another. After filling up the drenching bottle I wander down the aisle in front of the cows to pick the one pointed out by Brian. The cow catches a glimpse of the bottle in my hand and instantly fires a startled glare up at me. I clock that she’s seen it and there’s a second where both cow and man are frozen in a stand-off, each waiting for the others’ move.

The cow’s nerves get the better of her; swaying side to side, pawing at the ground, edging backwards and stepping forwards, craning its neck up and away from me. Now I’m standing face to face with it, both arms out stretched and mimicking the motion, side to side, looking for an opening. When I think I see it, I make my move. That is to say, I thrust my thumb and middle finger right up its nostrils.

Then there’s another second where I’m amazed at having my hand inside a cows face. Once I’ve made a mental note of how awesome this is I tuck the bottle of molasses under my right arm pit, yank on her nose, wrap my left arm over the top of her neck and grab the underside of her top lip on the opposite side. I let go of her nose and slide the bottle into my hand. This is the point where she really kicks off.

It’s now my job to, not only hold onto the head of a cow that definitely doesn’t want me to, but to overpower it with one arm, pry open its mouth, tilt its head up to open the gullet and upend a litre of tar-like syrup down it. She definitely doesn’t want me to.

It’s not uncommon for a cow to drag me over the barrier and pin me, with the force of a Car-Cuber, between herself and her neighbour, whom she is certainly in cahoots with. However, it’s a more regular occurrence for the cow to have me floundering with both legs airborne, one arm clinging around her neck, and the other flapping wildly dispensing molasses over me and everything else in the local vicinity. A timely flick of the neck would see me catapulted with a parabola’s trajectory against the unfortunately position breeze block wall.

4. Feeding the Calves – New born calves, for the first few days of feeding, must imbibe themselves on colostrum. It is the priority of the afternoon milking to collect this colostrum from the newly birthed cows in a specifically designated receptacle and ferry it over to the calves’ pens.

From being deposited in their pens in the morning to being corralled for feeding in the afternoon, the calves have collectively dedicated their time to decorating themselves and their surroundings in a staggering amount of excretion.Such was their dedication; a good number of them will have collapsed into an immobilized torpor.

This, therefore, requires some physical encouragement provided by some gentle rocking with the inside of the palm; and supplemented by a few stirring swipes with the outside. This technique would almost always render poor results but a better way was without the grasp of my temperament.

If I had made a success of raising the sleepers I would then need to direct them out of the pen and onto the ‘calfetier’: a task made all the more calamitous by the ice-like slick covering the wooden flooring – a residual effect of the previously mentioned calf waste – and the now unrestrained vim shown among the calves.

One man and eight calves produce a total of thirty-four legs; each one working with seemingly opposing objectives and at an alarming rate. A front leg might lurch forward while a hind leg splays outward; a knee might buckle while a hip joint locks; a body could collapse and cause a chin to meet with the floor; or a leg may rocket into the air and throw a head backwards, perhaps leaving it fixed between slats in the gate. This latter predicament is far less wearing when it happens to one of the calves.

It is outside the pen at the ‘calfetier’ that the true level of stubbornness in a young calf is displayed. Large amounts of time and effort are required to over-turn the natural impulse of a calf to look to an elder for nourishment.

Convincing them that the source of their unbridled excitement lies in drinking vast quantities of liquid and not in my crotch is to convince most women I know of the opposite.

If after completing all these jobs I was still able to call upon my bodily faculties to walk myself home unassisted, I could graciously call the day a roaring success.

After four months of debasing frivolities in New Zealand’s party capital, I decided it was time to leave Queenstown so I could do what I came to New Zealand to do in the first place: work as a Dairy Farmhand.

Even though, on the morning I left, I was nursing a hangover that felt like dysentery would be a favoured alternative, I took comfort in the promise of what the near future may bring. This was a day I had been quietly anticipating since the idea of coming to New Zealand sprouted in my head over a year ago.

Admittedly, leaving Queenstown and all its beautifully enticing appendages, not least of all the South American female backpackers that seemed to be so prevalent, didn’t feel like a natural thing to do at the time, but I knew I needed to experience something more rewardingly wholesome and in fitting with the real New Zealand.

I managed to get the job through an agricultural recruiting agency on the back of living for a number of years on a small holding in Wales and working as an assistant to my Engineer step father for a couple of summers between university years.

It wasn’t long before I realised I was in over my head. It came as a swift and not all that unanticipated realisation that feeding chickens and twice bailing hay is not an impressive background in farming, and, as anyone with even a paltry familiarity of the working world will admit, is far from enough experience to work for five months on a 900 acre working dairy farm with a herd 700 cows strong. A fact that my boss, Brian, became quickly assured of three minutes into my first day.

“Right, you can ride a two wheeler can’t you?” he said, confirming rather than asking. After deducing that he probably wouldn’t appreciate me admitting I couldn’t, I attempted circumvent the issue by cleverly replying “Uhhhmmm……..no”. It was early.

This must have only given him the impression that I’d forgotten whether I could or I couldn’t, a curious tactic when talking about riding a bike, but there we are. I attempted to change tack by ostensibly conveying concerned confusion as to where he could have got that idea from, while knowing full well it was from the job agency I had told I could a month before.

“OK, right, you can ride a 4 wheeler can’t you?” he asked, but this time with a tone and a facial expression that suggested only an idiot would say no to that question. I said no. After a short pause, while he came to terms with hiring a cretinous space waster, he half-heartedly asked “Tractor?” I didn’t offer an answer as much as slowly release a defeated breath from my inflated cheeks and raise an eye brow that told him all he needed to know.

That morning it became ominously clear the months ahead were going to be laden with an enduring sense of disappointment, chiefly dispensed by yours truly.

For someone who had never before worked on a dairy farm, it took quite a lot of focus and brain power (admittedly something I am not regularly accustomed to) in order to fully comprehend what my tasks involved and how they contributed to the overall continuity of the farm. Receiving instructions from Brian wasn’t quite as elementary as the two, usually, reciprocally conducive acts of him saying them and me hearing them would suggest.

Not wanting to say Brian had a limited vocabulary, although it seemed he would use words as if he was being charged by the letter. In trying to get his money’s worth he would cram them all into each sentence, while not being overly concerned with the trifling issue of making any sense whatsoever. Conversations with Brian would often leave me utterly perplexed and completely clueless.

One of his many mystifying instructions was to “go and spray the paddock halfway down the lane, that’s above the opposite field where it joins the back paddock next to the one that’s below itself”. That might not be entirely verbatim, but it was similar nonsense giving me a cerebral meltdown almost every day in the first few weeks on the farm

There were a number of things I found especially hard to get to grips with during the initial stages of my appointment in Tokoroa. Being in Tokoroa was one of them. It’s a moderately sized rural New Zealand town, situated in the Waikato region at the heart of the north island and surrounded by an unremitting landscape of absolutely nothing.

The farm itself is reached by a 20 minute car journey approximately 15km north of the town along Old Taupo Road. A journey that when going to the farm for the first time gave me my first real sense of what Tokoroa and the Waikato could offer.

As the evening crept in I was given the opportunity to survey my new habitat from atop a gently rising brae outside Brian’s wooden slatted farmhouse. The dwindling sun threw faint beams of twilight skipping across an endlessly undulating countryside that engulfed me on all fronts, before falling behind the silhouette of the Rangitoto mountain range to the west.

It was an undeniably tranquil and humbling setting that most would struggle not to appreciate, and I was suddenly smitten. However settling this brief moment of reverie was, it was to be the last one for several, several weeks.

Arriving at Nuku’alofa International Airport is a pleasantly unexceptional experience. Its runway is a grey score through sheets of chartreuse lawns mottled with tiny tufts of dark green, like balled cotton clinging to a jumper. The terminal building lies idly among a mesh of irregular palm trees, seemingly in a state of exhaustion.

As I stepped from the sterile chill of the aeroplane, the wall of thick air was dizzying to walk through and the heavy heat hung off me as a garment. It was early morning but already the sun had begun to cook the day. I trudged across the tarmac removing needless layers of clothes. The door marked ‘arrivals’ shimmered behind the haze rising in front of it and the ground appeared to swell below me. Everything here had a pulse.

Once inside, the relief of the shelter is complemented by the fact that you’re reminded by very little that speaks of an international airport. It was a relaxed and unaffected arrangement that proved a welcomed spin on the tedious chaos of most airport terminals. The general listlessness of the employees, the hand painted welcome sign above the immigration desks – which were two ragged book stands draped with grass skirts – and the official customs forms evidently designed on pic art were all indications of the casual island sentiment that permeates the attitudes of even the tautest of tourists.

The hostel which I was booked into, along with my travel buddy, Owain, was a basic affair but it offered an airport pick-up and a shuttle into town throughout the day. We were shown to our quarters at the end of a potholed dirt track behind the more agreeable looking accommodation at the front. As cement shells go, we couldn’t have much complained, but the mattresses could have doubled as doors and a hole in an overhead septic tank would have made a marked improvement on the shower.

As we took a few moments to make these considered appraisals a dark carpet of cloud rolled itself out across the heavens, too quick for either of us to notice before it emptied a torrent of rain that kept us confined to the common room until late afternoon.

Eventually the weather cleared and Owain and I wasted no time in venturing away from the hostel. With backpacks and water bottles we skipped down mud alleys, over coffee coloured puddles and through verges of messy St. Augustine grass; passed topless children chasing scrawny chickens; ducked under overhanging hibiscus flowers; and cleared onto the open main street. We turned and headed west towards the coast.

It wasn’t long before we approached the local market around the first bend. As we rounded the corner there seemed to descend a small second of peaceful silence; a quiet feeling of empty calm, like the moment right before you walk into a glass door. Except in this instance it wasn’t a pane of glass but a pack of five rabid dogs crowding the shop entrance. Each of them lifted their heads, turned and glared at us. We both froze, our breath stuck in our throats.

Only a few feet away from us was the biggest and most aggressive-looking: tufts of fur missing from its bloodied coat, shoulders like a shot putter and anvils for paws. It peeled back its top lip and let out a snarl that nearly made me collapse on the ground. Neither Owain nor I took our eyes off the dogs’ movements as they pawed at the dirt.

Owain – breath still trapped – took a tentative half-step backwards that sent the beasts into a wild fury. The biggest leapt forward into a torrent of guttural barks and ferocious fangs, strings of saliva tumbled from its mouth and its jet-black eyes protruded out its skull like bullets. Both of us were now back pedalling in to the street, considerably more concerned about avoiding a bite from this animal than getting T-boned by a bus. It forced us clean across the road.

We edged along the opposite side and watched the pack descend; they lunged and barked at each other as they were overwhelmed by their rage. An old and heavily dented people carrier tottered by us at a canter. Its engine coughing and spluttering mocked the scene, but distracted the dogs long enough for us to mark an ample retreat. Steadying our breath we doubled our pace, taking regular glances over our shoulders as we high-tailed it into the distance.

We had set off in search of a beach, wanting golden stretches of palm enclosed bliss scattered with satin skinned nymphs. But it seemed this rude introduction to Tonga proved a bit of a contradiction to that fantasy – at least for now.